Francesco Carraro shares his beloved collection

A Collector's Life

-

Francesco Carraro's home in Venice

Photo © Edward Barber

-

Francesco Carraro's home in Venice

Photo © Edward Barber

-

Francesco Carraro's home in Venice

Photo © Edward Barber

-

Como Teapot by Lino Sabattini for Christofle et Cie

Photo © Edward Barber

-

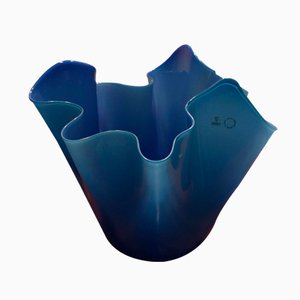

Carlo Scarpa for Venini

Photo © Edward Barber

-

Corrosi vases and Murrine Opache bowl by Carlo Scarpa for Venini

Photo © Edward Barber

-

Francesco Carraro's home in Venice

Photo © Edward Barber

-

Work by Joseph Cornell

Photo © Edward Barber

-

Napoleone Martinuzzi for Venini

Photo © Edward Barber

-

Yoichi Ohira vases

Photo © Edward Barber

-

The Grand Canal

Photo © Edward Barber

-

Francesco Carraro's home in Venice

Photo © Edward Barber

-

Francesco Carraro's home in Venice

Photo © Edward Barber

-

Francesco Carraro

Photo © Edward Barber

Francesco Carraro is famous in certain circles. The world’s most elite decorative and fine arts curators, dealers, and collectors know his Venetian home to be a repository of countless, highly prized works from the likes of Emile Gallé , Josef Hoffmann, Giò Ponti, Carlo Mollino, Alighiero Boetti, and Giorgio Morandi. The much-lauded Carlo Scarpa glass exhibition recently mounted at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art included a number of pieces borrowed from Carraro’s personal collection. And this is not unusual. Other pieces from Carraro’s collection have shown at MoMA and Tate, to name just a couple.

Ambra met the always dapper Carraro—he’s like a character out of a Visconti film—years ago through her gallerist mother. After admiring the Scarpa works at the Met, Ambra decided to visit this legendary aristocrat to hear the story behind his world-class collection.

Ambra Medda: Francesco, when did you start collecting?

Francesco Carraro: I started in 1966 while I was studying music in Berlin. I was away from my family for the first time, and I began buying these small, inexpensive glass objects—just for the pleasure really. I still have two little drinking glasses from that time.

By 1979, I had acquired—for very little—many Émile Gallé pieces, which I showed to Philippe Daverio [famed Italian art critic and dealer]. He put them up on auction, and a number of my pieces sold for ten times what I paid. Daverio came to my house and said, “You have an eye. Why do you keep buying generic glass? Why don’t you buy better pieces?” So I started buying more important Venetian glass. Soon I was going to New York five times a year—in the 1980s—to do the auctions. Glass was still quite affordable, and there was so much of it.

AM: Were your parents collectors?

FC: No. I didn’t know my mother, because she died when I was three years old. And my father had only a third grade education and wasn’t interested in beautiful things. My brother dabbled in paintings from the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s. And he acquired some really nice things, like Saligno and De Chirico. I was much more curious, of course.

AM: Yes, it’s clear when I look at your home that you have spent your whole life in pursuit of beautiful objects.

FC: [laughing] I have accumulated a lot—too much to have on display all the time—but I love to look at beautiful things and be surrounded by them. I want to really live with the things I buy.

AM: To enjoy them…

FC: Yes, to enjoy them.

AM: Are there particular pieces from your collection today that you are especially fond of?

FC: It’s hard to choose… The things I bought from Lillian Nassau in the 1980s mean a great deal to me. Lillian was the first to create a hype for Tiffany lamps with her gallery on 3rd and 57th in New York. She lived to be ninety years old; she’s quite a historically significant figure.

I loved her because she was fun and smart and spoke French, which was convenient for me. Ninety percent of her merchandise was Tiffany, but the other 10% was really unusual, curious pieces, including works by Venini. She understood my taste and would send me Polaroids of things she thought I would like. And every time I went to New York, she would assemble pieces in tune with my interests. I bought a lot from her—things that today cost twenty, thirty, forty thousand, but back then were only two or three hundred dollars.

AM: What were some of the stellar pieces you bought back then?

FC: A 1925 porcelain centerpiece by Giò Ponti. Here, I can show you. [Gets up and points out the pieces.] This was a set used by Italian embassies for official receptions. This is one of the bigger sets.

AM: Wow! How marvelous! And in perfect condition!

FC: Perfect! I love Ponti porcelain, especially from the 1920s and ’30s. I also really love Mollino and Gallé. I have some Josef Hoffmann pieces from Vienna that are outstanding—famous and beautiful. I wish I had bought some pieces by Macintosh and Gaudì, but they were already very expensive back then.

AM: Are there any pieces that you’ve parted with that you regret?

FC: A Lucio Fontana painting that I got for very little. It was not the most beautiful, but it was nice and important. I needed money; despite owning a factory with thousands of workers, no one would give me cash, so I sold it. But I’ve had good luck, too.

AM: Like what?

FC: Ten years ago, I fell in love with a Morandi painting. I sold stock in my family business to pay for it. Now it’s worth a lot. I sold my few stocks, and this was my great fortune. Now I have a stipend like an A-level footballer, but without running, without training. I’m like a soccer player of luck. [laughing]

I’ve always liked money a lot—but just to spend it, not to keep it. When I sold the stocks, a bank director—from a good bank in Padua—invited me to his office and said, “I know you must be thinking about investment.” And I said, “What? Me? I’m investing in spending.” Some people have money, and they don’t know what to buy. It’s a shame. Sometimes they ask me for advice, but I tell them, “If you don’t know what you like, I can’t help you.” [laughing]

AM: So your collection is not at all motivated by investment?

FC: I never thought about it. On the rare occasions I tried to buy on speculation—to buy and then resell for much more—I usually lost. The things that brought me the most fortune were the things I bought because I loved them. The things I bought from passion are still with me. Some things were expensive, but I love them. I enjoy owning them, and I don’t sit around watching the price go up and down.

AM: So was the Morandi your most fortunate acquisition?

FC: No, in terms of value, the Boetti map here above our heads was more fortunate for me. It’s worth twenty-five times what I originally paid. I’ve had offers for some of my pieces—even outrageous offers—but I didn’t accept.

AM: Why not?

FC: Because what would I do? Put a check on the wall in place of the piece? No, I’m not interested.

AM: I understand you’re working on a book about your collection. Is that right?

FC: An American called Annie Schlechter came to photograph everything. She made a presentation of the house and all the objects. She’s quite good. I’m not sure when the book will come out, though.

AM: I’m looking forward to seeing it. What are your plans for your collection in the future?

FC: I will probably start a foundation, maybe with the help of my nephews, in my hometown of Padua. Venice is over. It’s a Disneyland. It’s very sad.

AM: Venice does seem overwhelmed with tourists.

FC: It’s expensive. And for young people, it’s not very attractive. Everywhere you go they rob you. It costs 30 Euros a day just to park—and you know the young people like to be mobile and move with a car. They prefer to go to Mestre or Padua. And so do I. I want these pieces to continue to have a life, their beauty to be appreciated for generations to come.

This interview has been translated from Italian, edited, and condensed.

-

Introduction by

-

Wava Carpenter

Seit ihrem Studium in Designgeschichte an der Parsons School of Design hatte Wava schon in vielen Bereichen der Designkultur den Hut auf: sie lehrte Designwissenschaft, kuratierte Ausstellungen, überwachte Auftragsarbeiten, organisierte Vorträge, schrieb Artikel und erledigte alle möglichen Aufgaben bei Design Miami. Wava lässt den Hut aber im Büro – auf der Straße bevorzugt sie ihre Sonnenbrille.

-

-

Interview by

-

Ambra Medda

Ambra is a passionate, seasoned curator, who facilitates great design through innovative collaborations between designers, artists, brands, and institutions. Among many other things.

-

Designbegeisterte hier entlang

Italienische Tischlampe von Venini, 1950er

Tolboi Stehlampe von Venini, 2000

Fazzoletto Vase von Fulvio Bianconi für Venini, 1983

Italienische Calze Wandleuchten von Carlo Scarpa für Venini, 1960er, 2er Set

Italienische Hängelampe von Massimo Vignelli für Venini, 1960er

Italienische Hängelampe aus Glas von Venini, 1950er

Italienische Wandleuchte aus Glas von Venini, 1960er

Kronleuchter in Rot & Weiß von Paolo Venini für Venini, 1960er

Italienischer Kaskaden-Kronleuchter von Venini, 1960er

Große Italienische Sechseckige Poliedri Deckenlampe von Carlo Scarpa für Venini

Vintage Glas Kronleuchter von Venini, 1940er

Fungo Tischlampe von Massimo Vignelli für Venini, 1950er

Vintage Kristallglas Kronleuchter von Venini

Mundgeblasener Glas Kronleuchter von Toni Zuccheri für Venini, 1960er

Gestreifte Hängelampe von Massimo Vignelli für Venini, 1955

Pulegoso Wandlampen aus Glas von Venini, 2er Set

Murano Glas Kronleuchter von Carlo Scarpa für Venini, 1950

Italienische Mid-Century Deckenlampe von Venini, 1960

Röhrenförmige Murano Deckenlampe von Venini

Mid-Century Kronleuchter von Venini, 1960

Italienische Deckenlampe von Venini

Deckenleuchte von Valdimar Harðarson für Venini, 1960er

Italienischer Mid-Century Modern Kronleuchter von Venini, 1960er

Francesco Carraro in conversation with Ambra Medda

© Edward Barber

Francesco Carraro in conversation with Ambra Medda

© Edward Barber

Centerpiece by Giò Ponti

© Edward Barber

Centerpiece by Giò Ponti

© Edward Barber

Work by Josef Hoffmann

© Edward Barber

Work by Josef Hoffmann

© Edward Barber